An excerpt from Mattijs Diepraam's fantastic article on rear/mid engine race cars.

The undoubted pre-war highlights among the rear-engined single-seater racing machines were the ultra-successful übercars built by the Auto Union racing department. That is, if you could call them highlights when the opposition comprised of a strange collection of Indy specials (more on them later) and the earlier Tropfenwagen.

While the Auto Unions were at the pinnacle of world motor racing for over five years it took a long time before another European designer felt the need to follow in Porsche’s footsteps to create a mid-engined racing car of his own. (Although we should not forget that Porsche himself, after severing his Auto Union ties, made a rear-engined proposal to Mercedes for the 3-litre regulations.)

The man in question was Wifredo Ricart, the willful designer at Alfa Romeo, which had seen its previous 8, 12 and 16-cylinder counter efforts against the almighty Germans fail miserably. Alfa Corse were also running terribly late with their latest Grand Prix challenger, the 162, which later turned out to be stillborn. And then the new 1.5-litre s/c GP regulations for 1941 onwards became known.

There was initial scare, as Mercedes had upstaged the competition by winning the 1939 Tripoli GP out of the blue with their W165s, and this was blown up into a real fright when the new 'baby' Auto Union Type-E was rumoured to have an engine capable of producing well in excess of 300hp at a crank speed of 9000rpm. Clearly the then serving Alfa voiturette, the highly successful 158 'Alfetta' with its straight-eight engine only producing 225hp at 7600rpm, wasn't going to be a match. Drastic measures were needed.

While the Auto Unions were at the pinnacle of world motor racing for over five years it took a long time before another European designer felt the need to follow in Porsche’s footsteps to create a mid-engined racing car of his own. (Although we should not forget that Porsche himself, after severing his Auto Union ties, made a rear-engined proposal to Mercedes for the 3-litre regulations.)

The man in question was Wifredo Ricart, the willful designer at Alfa Romeo, which had seen its previous 8, 12 and 16-cylinder counter efforts against the almighty Germans fail miserably. Alfa Corse were also running terribly late with their latest Grand Prix challenger, the 162, which later turned out to be stillborn. And then the new 1.5-litre s/c GP regulations for 1941 onwards became known.

There was initial scare, as Mercedes had upstaged the competition by winning the 1939 Tripoli GP out of the blue with their W165s, and this was blown up into a real fright when the new 'baby' Auto Union Type-E was rumoured to have an engine capable of producing well in excess of 300hp at a crank speed of 9000rpm. Clearly the then serving Alfa voiturette, the highly successful 158 'Alfetta' with its straight-eight engine only producing 225hp at 7600rpm, wasn't going to be a match. Drastic measures were needed.

Of course everybody at Alfa Romeo knew of the handling difficulties that a rear-engined lay-out presented, and that it needed a special talent such as Rosemeyer to eek out the full potential of the car, especially with the driver having to sit far forward in the nose, unable to quickly feel the handling changes that a swing-axled rear suspension would transfer to him.

Still, the intrinsic advantages of an engine positioned behind the driver had become apparent to Ricart, the Spaniard who had succeeded Lancia-bound Vittorio Jano as the Portello design team's top man. Amongst others, his crew consisted of the talented Gioacchino Colombo, who had been responsible for the Alfetta and later joined Ferrari and the revived Bugatti team (more on that in part 2), and Luigi Bazzi, who did the famous Bimotore. Ricart entrusted the former with the detailed design of the rear-engined car.

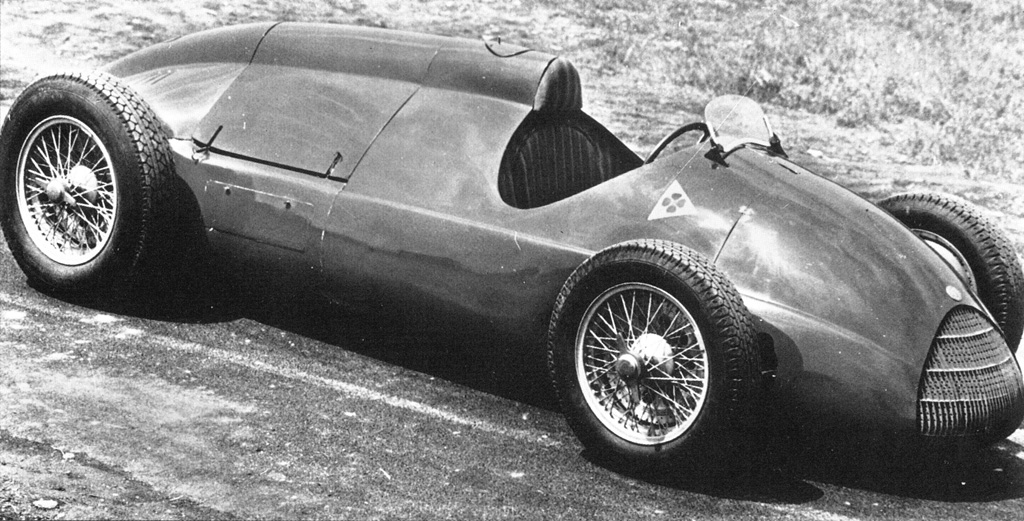

So when the new 1.5-litre supercharged Grand Prix formula was laid down, Colombo drew an Auto Union Type D-inspired racing car to rival the Mercedes W165 and Auto Union Type E. The 512 used a flat-twelve DOHC engine with two-stage supercharging. Tested on the bench it had peaked at 370hp at 9000rpm while averaging 335hp at 8600rpm. That was considerably above the rumoured Auto Union target, giving cause to optimism in the Portello works.

Still, the intrinsic advantages of an engine positioned behind the driver had become apparent to Ricart, the Spaniard who had succeeded Lancia-bound Vittorio Jano as the Portello design team's top man. Amongst others, his crew consisted of the talented Gioacchino Colombo, who had been responsible for the Alfetta and later joined Ferrari and the revived Bugatti team (more on that in part 2), and Luigi Bazzi, who did the famous Bimotore. Ricart entrusted the former with the detailed design of the rear-engined car.

So when the new 1.5-litre supercharged Grand Prix formula was laid down, Colombo drew an Auto Union Type D-inspired racing car to rival the Mercedes W165 and Auto Union Type E. The 512 used a flat-twelve DOHC engine with two-stage supercharging. Tested on the bench it had peaked at 370hp at 9000rpm while averaging 335hp at 8600rpm. That was considerably above the rumoured Auto Union target, giving cause to optimism in the Portello works.

The car itself followed Auto Union lines by placing the fuel tank directly behind the driver and positioning the gearbox behind the back axle. The car's twin-tube ladder frame was suspended by wishbones at the front and a De Dion set-up at the back, on top of which low-slung, bulging bodywork was placed.

The detailing was meticulous but also very time-consuming, especially since Italy was becoming more involved in World War II by the month. It is amazing, however, that development carried on well into the war and that the finished product was tested as late as 1943, although parts testing had already started in the summer of 1940.

Some of the tests took place on the Milan-Varese autostrada, and it was on the early morning 19 June 1940, during one of these tests, that Alfa's faithful tester Attilio Marinoni was killed as his 158 carrying the 512 rear suspension hit an unsighted lorry during a takeover manoeuvre. Consalvo Sanesi, the mechanic-turned-tester, tested the car many times at Monza and predictably reported that it was a real handful. More tellingly, however, was his conviction that the Alfetta was quicker. On the other hand, Carlo Pintacuda was said to be much more flattering about the 512's road behaviour.

In the end we will never know. Along with the other Alfa Romeos the 512 was stored in the famous cheese factory but the only thing the racing world heard of it in 1946 were its detailed design plans issued in an Auto Italiana article. Although post-war Alfa threatened to bring out the 512s as soon as the Alfettas got beaten, they never needed to and never did. And it remains to be seen if they would ever have been able to.

The detailing was meticulous but also very time-consuming, especially since Italy was becoming more involved in World War II by the month. It is amazing, however, that development carried on well into the war and that the finished product was tested as late as 1943, although parts testing had already started in the summer of 1940.

Some of the tests took place on the Milan-Varese autostrada, and it was on the early morning 19 June 1940, during one of these tests, that Alfa's faithful tester Attilio Marinoni was killed as his 158 carrying the 512 rear suspension hit an unsighted lorry during a takeover manoeuvre. Consalvo Sanesi, the mechanic-turned-tester, tested the car many times at Monza and predictably reported that it was a real handful. More tellingly, however, was his conviction that the Alfetta was quicker. On the other hand, Carlo Pintacuda was said to be much more flattering about the 512's road behaviour.

In the end we will never know. Along with the other Alfa Romeos the 512 was stored in the famous cheese factory but the only thing the racing world heard of it in 1946 were its detailed design plans issued in an Auto Italiana article. Although post-war Alfa threatened to bring out the 512s as soon as the Alfettas got beaten, they never needed to and never did. And it remains to be seen if they would ever have been able to.

More Alfa Romeo on Axis

No comments:

Post a Comment